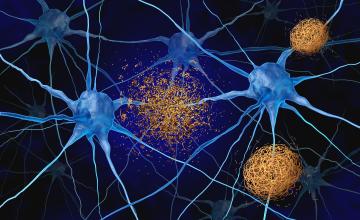

On November 3, 1906, the German clinical psychiatrist and neuroanatomist Alois Alzheimer reported “A...

Chances are you already know us

Over the years, since our foundation in Japan in 1950, we have built a strong tradition of innovating, developing, manufacturing and marketing high-quality in vitro diagnostics testing solutions worldwide.

The acquisition of Centocor Diagnostics, CanAg Diagnostics and Innogenetics have further bolstered our capabilities and expertise in various clinical areas.

Today, working closely with one of the world’s top commercial laboratories (SRL, Inc.), another entity within the H.U. Group, Fujirebio combines expertise and experience for the diagnostics market that is more potent than ever.

Product categories:

Products by diseases and disorders:

News & Events

View all news & upcoming eventsInsights in the world of Fujirebio

Aug 27, 2025

The Future of Alzheimer's Disease Diagnosis

What is the future of Alzheimer's disease diagnosis?

Two anti-amyloid drugs are now available to patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or mild...

Jun 25, 2025

Everything You Need to Know About Amyloid Presence and Alzheimer’s Disease-modifying Therapies

Confirming amyloid pathology before administering Alzheimer’s disease-modifying therapies.

Approximately seven million Americans are currently living...

May 20, 2025

Video - The Scientist Symposium: Understanding Disease Through Biomarkers

The Evolution of AD Diagnosis: The Role of Biomarkers

Biomarkers are transforming the landscape of disease detection and diagnosis—especially in the...

May 8, 2025

Modern Alzheimer’s Diagnosis: What Clinicians Need to Know About Biomarkers and Staging

What PET scans, CSF assays, and blood tests reveal about Alzheimer’s — and how the A/T/N framework supports earlier, more accurate diagnoses.

Alzheimer...

Nov 13, 2024